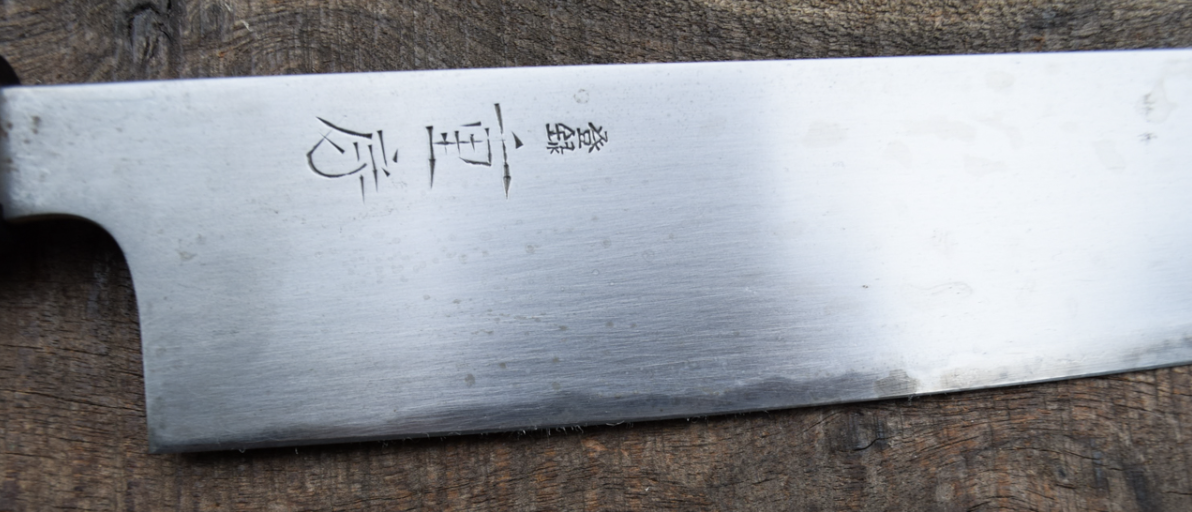

As we discussed in our first deep dive, the Shigafusa (Shig) gyuto is a general-use knife with many of the same characteristics of the French chef. In terms of feel, the main difference here is the fulcrum is forward of the handle by about an inch rather than immediately after the handle as on the Sabatier. To be clear, the knife in the picture above is not built by us.

The handle also has a much different look than the handle of the Sabatier. (In fact, classically, the 'knife' with many Japanese makers refers only to the blade rather than the blade and handle combined). This particular handle is made of a very light unstabilized wood called Ho wood, a type of magnolia, and the ferrule (black part) is made of cow horn.

The handle and blade are arranged so that the handle can be removed or replaced and the knife cleaned. The blade is held in the handle by friction: the tang of the knife is placed between the two sides of a split dowel which are squeezed together by the ferrule.

Under the hood, this Shig is very different from the Sabatier we discussed in the first deep dive. The blade is composed of a hard, high-carbon center clad on the sides by two soft pieces of iron. This process is called san mai. The core steel is hardened to something in the neighborhood of a 61-63 Rockwell Hardness - as opposed to a hardness in the mid-50's for the Sabatier. You can see the distinction between the core steel and the cladding along the edge in the photo below.

One of the aspects of the Shig gyuto that distinguishes it among its contemporaries is that the spine and choil are rounded for comfort which is not the case on many traditionally built Japanese knives. You will also notice that the spine, after immediately tapering from the handle, has a consistent dimension all the way to the tip. This lack of taper is a marked difference from the Sabatier we talked about last month which has a strong taper and a thin flexible tip.

Okay. What does all this mean? Here is the meat of the matter (PUN :)): while the knives are designed to cut the same sorts of food, i.e., Western cuisine, they approach this cutting from two extremes.

The first extreme: for the French chef, its design prioritizes durability over edge-holding (strength). You can do anything with this knife up to and including grouting your bathroom tile. I defy you to break this knife on anything. You could finish your work on the tile, wipe the knife down, hone it, and start work on dinner.

The main trade-off here is edge-quality. Because of the relative softness of the steel, the knife requires frequent and aggressive honing during food prep. (Luke will discuss honing further when he dives into sharpening in the next deep dive). This frequent honing shortens the life of the knife and makes the knife cut less and less well over time as the thin edge moves into the thicker areas of the blade.

The other extreme: the Gyuto's design opts for strength. The relative hardness of the steel and thinness of the cutting edge mean that dressing and redressing the edge during prep isn't really a thing. You can get this edge very keen, and that keenness will last. Sharpening this knife takes more skill and time, but the quality of the edge can be quite high.

But, while the cladding will prevent the knife's breaking, the thin, hard edge will chip easily. This is not the knife for acorn squash stems or any kind of lateral stresses. Would you take your Porsche into the woods? Probably not.

So what did we do about all this? Have a look at our Gyuto Study gallery and find out :)

Thanks for following along.

-David